Former Maryland Rep. John Delaney, along with fellow moderates Rep. Tim Ryan and former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, all sought to defend their plans to build on the status quo -- Obamacare -- and portray Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren on health care as too far to the left. They argued that "Medicare for All," which would establish a national health insurance system and essentially eliminate private insurance, would also dash Democratic prospects in the 2020 presidential election.

That argument, over the policy itself and its political implications, has become the bloodiest battleground of this Democratic primary. Health care emerged as a winning issue in the 2018 midterms, but the Democratic Party remains divided over how to proceed in 2020 -- at the same time as the Trump administration is waging a court battle to undo the Affordable Care Act, President Barack Obama's signature health care law.

Sanders and Warren are the only two top-tier candidates to back Medicare forall without apology or qualification. Former Vice President Joe Biden is a vocal opponent, while others, like California Sen. Kamala Harris and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, support plans that would move the American health care system in that direction but preserve some space for the private insurers to operate.

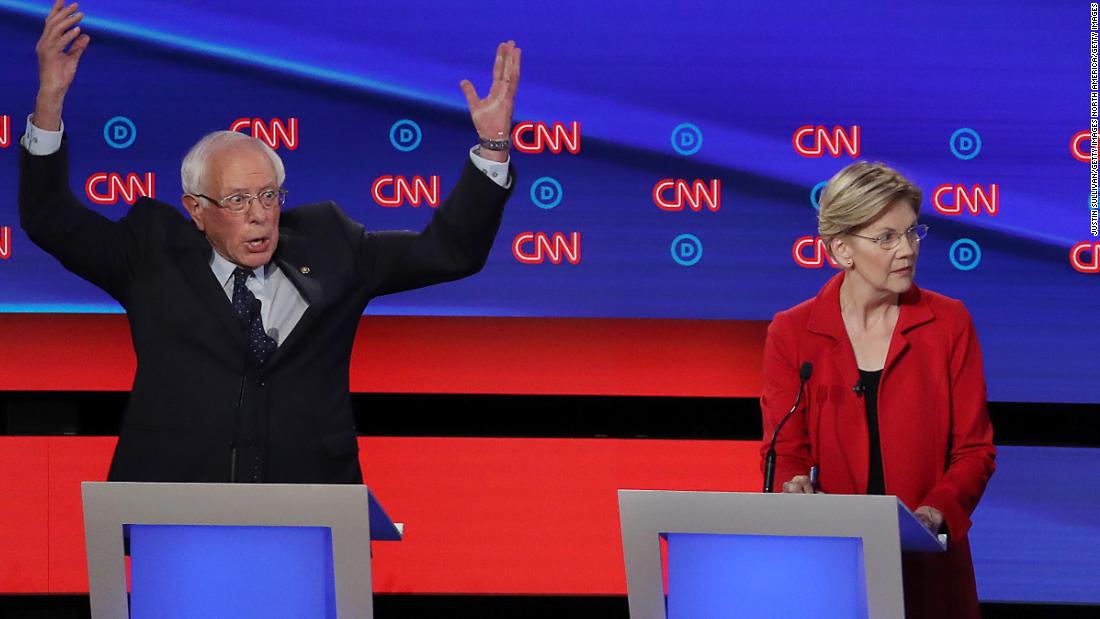

But Sanders and Warren came prepared -- and appeared energized by the chance to defend the bedrock progressive policy plan. Warren condemned Delaney's criticism as "Republican talking points," and Sanders suggested the former House member misunderstood the basic goal of the plan, which is to both change the way Americans both receive and perceive health care.

The debate was heavy on substance, demonstrating the ideological divide at the heart of the contest.

Delaney sought to highlight the potential problems that Medicare for All could create for the nation's health care system, saying that Medicare pays much less than private insurance. Hospitals, particularly rural ones, couldn't afford the cut in reimbursements, he said, brushing aside Sanders' retort that hospitals will save money because they won't have to do as much billing and administrative tasks.

"I'm the only one on the stage who actually has experience in the health care industry," said Delaney, who owned a health care firm and co-founded a lender to health care companies. "And with all due respect, I don't think my colleagues understand the business."

As he finished his sentence, Sanders shot back: "It's not a business."

Sanders also pushed back against Ryan with a line that, before the debate had ended, his campaign had already slapped on a bumper sticker.

Asked if he could promise union workers that Medicare for All would provide the same quality benefits they have now, Sanders argued Medicare for All would improve on them.

"You don't know that, Bernie," Ryan jumped in.

"I do know," Sanders stormed back. "I wrote the damn bill!"

Warren, too, made a point of hitting out against the arguments against Medicare for All, lamenting moderates' use of what she described as "Republican talking points" of warning that its implementation would throw people off their health care -- without taking into serious account the system they would land in. Delaney set off Warren when he said Democrats risked becoming "the part of subtraction" by enforcing an end to private plans.

"Let's be clear about this," Warren said. "We are the Democrats. We are not about trying to take away health care from anyone. That's what the Republicans are trying to do."

It was left to the author Marianne Williamson, an ally to Sanders and Warren on most policy issues, to offer one of the more convincing lines of skepticism.

"I do have concern about what the Republicans would say," she said. "I do have concern that it will be difficult. I have concern that it will make it harder to win, and I have a concern that it'll make it harder to govern."

Advocating for his bill, Sanders called the health care system "dysfunctional" and argued that a single-payer regime would provide stability for the health care industry. He praised the system in nearby Canada as a model, noting that it spends half of what America does on health care and that "when you end up in a hospital in Canada, you come out with no bill at all."

CNN moderator Jake Tapper might have caused the most uncomfortable moment for Warren when he asked whether her version of Medicare for All would include a middle class tax hike, as Sanders has said his bill would require.

"So giant corporations and billionaires are going to pay more. Middle-class families are going to pay less out of pocket for their health care," Warren said. That's the nut of Sanders' answer when he gets the question. But Warren was less direct. Given another chance to address if taxes would go up, Warren would only reiterated that "total costs" for middle-class families would go down.

Moderates seek to make a mark

Though they were pinned back by Sanders and Warren much of the night, the moderates did not come unprepared -- or without alternative plans of their own.

Some opponents of Medicare for All coalesced around the idea of strengthening the existing federal health-care law -- the Affordable Care Act as signed into law by former President Barack Obama -- through a government-backed insurance plan, otherwise known as the public option.

Among the supporters of that idea were Hickenlooper, Bullock and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who called it a "better way" to reach universal coverage. Biden, who debates on Wednesday night, has also hinged his plan on that promise. Klobuchar noted that not only did Obama advocate for a public option when he was president, but Sanders, as well, supported a recent bill that would implement the idea.

Bullock noted that it "took us decades and false starts" to pass the Affordable Care Act. "So let's actually build on it," he said.

Others, like former Texas Rep. Beto O'Rourke, argued for a hybrid plan that would place uninsured and underinsured Americans on Medicare. Delaney said his plan would provide universal health care with "choices."

But at the heart of those proposals was an argument -- at times explicit, other times implied -- that Medicare for All would be a loser for Democrats in a general election.

Leading that charge was Delaney, who said the Democrats threatening to take Americans off their private health plans -- no matter what waited on the other side -- were courting electoral disaster.

"My dad, the union electrician, loved the health care he got from the IBEW. He would never want someone to take that away," Delaney said. "Half of Medicare beneficiaries now have Medicare Advantage, which is private insurance, or supplemental plans."

Bullock echoed Delaney, suggesting Medicare for All would "[rip] away quality health care from individuals." Hickenlooper argued for the preferable health-care solution "would be an evolution, not a revolution." And Buttigieg brought up his "Medicare for All Who Want It" proposal to give Americans the option to change without kicking people off their existing plans.

The South Bend mayor, who has staked out a middle ground between the progressives and moderates like Delaney and Hickenlooper, scored some points later on as the debate-within-the-debate dragged when he advised the field to pay less attention -- and worry -- to how Republicans might try to weaponize the Democratic debate against them.

"If it's true that if we embrace a far-left agenda, they're going to say we're a bunch of crazy socialists. If we embrace a conservative agenda, you know what they're going to do? They're going to say we're a bunch of crazy socialists," Buttigieg said.

"So let's just stand up for the right policy, go out there and defend it."

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren pounce on 'Medicare for All' critics in Detroit debate"

Post a Comment