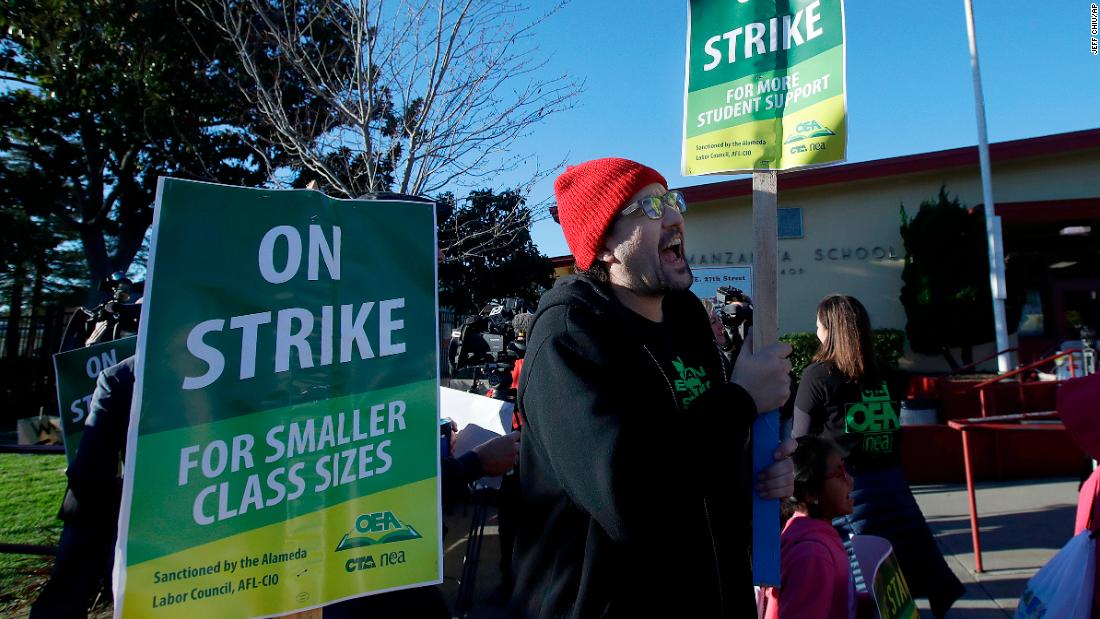

They've gone on strike in Denver, Los Angeles, Oakland and throughout West Virginia this year. They walked out in Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oklahoma and West Virginia last year. They've rallied in Georgia and Virginia.

Donald Trump Jr., the President's son, seemed to invoke striking teachers during a speech last month in El Paso, Texas, when he dismissed "these loser teachers that are trying to sell you on socialism from birth."

While the strikes require solidarity, the reasons for them range from salaries and benefits to school infrastructure and class size to charter schools.

Each of these situations is unique and has its own local concerns, but each also shares the underlying issue of how America should compensate its teachers and educate its children.

The national takeaways, according to Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, are that schools have been underfunded for years, that teachers have had enough and that parents are behind them.

"Nobody believes that striking is a first resort," she said. "It is a last resort. Nobody is strike-happy. But they get to it."

Teacher salaries nationwide are down compared with recent decades. Adjusting for inflation, they've shrunk 1.6% nationwide between 2000 and 2017, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, which compared the average annual salaries of teachers since 1969. US wages more generally have risen in that time, according to a Pew review of BLS statistics.

In some states that saw recent strikes, such as Arizona and North Carolina, salaries are down more than 10% before teachers fought for increases.

Salaries are up in that time frame in California, but the cost of living is up much more in a place like Oakland, where teachers are currently striking and the theme in reports from the city is that teachers can't afford to live there anymore. It's not too far a leap from that frustration with inequality to the local backlash and activism that drove Amazon from its plans to build part of its HQ2 in Long Island City in New York.

But the average salaries do not tell the whole story, according to research from Sylvia Allegretto of UC Berkeley and Lawrence Mishel at the Economic Policy Institute, a think tank that focuses on low- and middle-income workers. They have documented the erosion of teacher salaries compared with other similarly educated workers. Calling this erosion a "wage penalty," they argue that female teachers make 15.6% less than comparably educated women and that male teachers make 26.8% less than comparably educated men. It is true that teachers in most places get better benefits than many other workers, but benefits make up a larger portion of their compensation than for other workers and are no longer enough to offset their lower wages. The five states with the largest wage penalties for teachers, they found -- Arizona, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Colorado and Virginia -- all experienced protests or strikes in 2018. But there is a wage penalty for teachers in every single state, according to their study. California as a state has among the lowest wage penalties, but Los Angeles and Oakland also has among the highest costs of living in the country.

The larger point of Allegretto and Mishel is that states have chosen tax cuts over teachers, since most of the states with the largest reductions in education funding enacted tax cuts between 2008 and 2016.

NPR profiled Oklahoma's Teacher of the Year for 2016, who become an activist for more education funding before finally deciding to leave the state for nearby Texas. Oklahoma education funding per pupil is among the lowest in the country and has not kept pace with inflation.

And it's not just salaries that have the teachers picketing. In West Virginia, after a successful strike over salaries last year, teachers picketed this year to fight a charter schools bill.

Weingarten says the sheen of school choice has faded in recent years.

"The shiny object is not so shiny anymore," she says. And to her, the beginning of this new wave of teacher activism goes back to Trump's appointment of Betsy DeVos as his education secretary. DeVos has sought more federal funding for things like private school vouchers and less for public school systems.

This is not a traditionally partisan issue. Some Democrats, like New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who prides himself on being the only inner-city resident running for president, has been an advocate for school choice programs.

In Oakland this year, in addition to a 12% pay increase over three years, they want more support in the form of counselors and nurses for students. The district says it is broke can't afford more than a 5% increase when three-quarters of its students get help buying lunch.

Conservatives like Josh McGee from the Manhattan Institute have argued that teacher benefits -- in particular, pensions -- are to blame because they eat up a growing portion of education dollars. While spending on education has been cut in the years since the Great Recession, they'll point out, it had been growing for decades prior.

As Neal McCluskey at the CATO institute points out, there was a dip in education spending per pupil after the Great Recession, but it followed a more-than doubling of education spending per pupil since the 1970s.

They point to the growth of benefits for teachers as a reason for current shortfalls.

Weingarten argues that schools are doing a lot more, from providing meals to needy children to career training.

"We expect public schools to do everything right now," she says. "We've expected them to basically be the only institution in America that is about the aspirations of every single child."

Union power waning

This is also a story about unions. Teachers unions are leading the strikes in every one of these places.

There are two industries that continue to see extremely strong union representation in the US. Both protective service (police, firefighters) and education occupations have unions that represent more than 37% of employees, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics -- far more than any other occupations.

No private-sector industry listed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics approaches even 20% union representation. More than a third of public-sector employees at the federal, state and local level are represented by unions.

The 22 states that still allowed unions to collect fees from nonmembers who benefited from their collective bargaining agreements were stung by a Supreme Court decision in 2018 that said those fees violated the First Amendment. The power of public-sector unions, as a result, could fall in coming years.

Look no further than Wisconsin, where, after the state government limited collective bargaining for public employees in 2011 -- which at the time led to protests and ultimately an unsuccessful effort to recall then-Gov. Scott Walker -- teacher salaries dropped by more than 2% over a number of years and the value of teacher benefits plummeted more than 18%, according to a 2016 report by the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

Weingarten says unions have adapted to the Supreme Court decision, which presented them with an existential threat, by focusing more on a sense of community among teachers.

"We prepared in a way that fundamentally transformed our unions from an entity that most of our members saw as transactional to an entity that most of our members saw as communal," she said.

Public support for teachers, mixed voter support for funding

The curbing of union power in West Virginia in 2016 did not stop teachers there from striking. Nor in Oklahoma, which, since strikes last year, has considered legislation to make it illegal for teachers to walk off the job.

Part of the reason for that is Americans generally back the teachers, according to recent polling.

Seventy-eight percent of Americans said teachers don't make enough money, according to an April 2018 poll by The Associated Press/NORC Center. Fifteen percent said teachers make the right amount and 6% think they make too much. That's a increase in Americans who think teachers are underpaid; it was 57% in a similar 2010 poll conducted by AP.

Almost all Democrats -- nearly 90% -- said teachers are underpaid in the AP poll, compared with 78% of independents and a still-solid 66% majority of Republicans.

There is majority support -- but just barely, at 52% -- among Americans for teachers leaving their classrooms to strike.

Support for actual education funding, however, can be mixed, particularly statewide. Voters in Colorado in November rejected the largest proposal to hike state taxes by $1.6 billion to fund state schools. Voters also rejected funding measures in Missouri, Oklahoma and Utah. But according to a review from the Center for American Progress, voters in other states, including Maryland, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Maine, Montana and New Mexico approved $884 million in new state revenue. Georgia's voters moved toward raising funds through a sales tax referendum.

Even more funds were directed toward education at the local level. In Wisconsin alone, despite the statewide cuts over the course of years, 77 local ballot initiatives were approved by voters this past November, according to Milwaukee's Journal-Sentinel. Voters approved raising some local property taxes, such as in a district outside Milwaukee, and add more than a billion to education funding across the state.

Look for this issue to play a role in 2020. Trump Jr. seems to see socialism in the strikes. His dad, somewhat incredibly, has not weighed in on the strikes, but has made socialism a key element of his pitch against Democrats. Some Democrats have rallied behind a Green New Deal proposal that includes mention of new protections for union workers and the much larger debate over what role the government should play in daily life.

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why teacher strikes are touching every part of America"

Post a Comment