Everyone who picked up -- it was evening, and a few of the calls went to voicemail -- had two things in common: They had recently donated $25 or less to Warren's presidential campaign, and they couldn't believe that it was the Massachusetts Democrat on the line.

"No way. Get out of town," Grace, a graduate student in Alaska, blurted out.

"Oh my goodness," Matt, an Iowa resident, said with a laugh. "My wife is sitting here. Her jaw just dropped."

CNN recently sat in on one of Warren's "call time" sessions with small-dollar supporters, just days after she declared that she would not participate in any fundraisers, dinners, receptions or phone calls with wealthy donors during the primaries. She is already rejecting donations from PACs and federal lobbyists -- all part of her campaign's anti-corruption and anti-big money themes.

Warren's advisers say their strategy is about building a solid foundation for the long-haul. The time saved by skipping glitzy fundraisers and call times with deep-pocketed donors is being invested in more organizing events and town halls, they say. Warren has traveled to eight states -- Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Georgia, Nevada, California, New York and Texas -- as well as Puerto Rico so far this year.

There is time set aside every week for phone calls and meetings with grassroots supporters and small-dollar supporters, according to advisers, who say Warren has made hundreds of grassroots calls so far this year.

In an interview with CNN, Warren described these conversations as some of the best opportunities to get a raw sampling of the issues that are most pressing for voters. It's the same benefit, she said, of the photo lines that she does after every campaign event.

"I get to hear what's right at the top of their minds. But also, I love it because it's -- just for a moment, a spark of this is how democracy is supposed to work," Warren told CNN. "You know, in life, there are some people who have more money, there are some people who have less money. But everybody should have an equal share of our democracy."

In calls that lasted no more than a few minutes each, Warren spoke with Matt, the president of a childcare association in Iowa who wanted to discuss play-based learning; Sharifa, a teacher in California worried about lower-income students who can't afford to participate in certain school activities; and Grace, the Alaska student eager to discuss the country's mental health care system.

And Warren was quick to put Logan, a college student in Idaho who works at a McDonald's, on the spot.

"So what do you learn from working at McDonald's?" she asked.

"Um, what do I learn?" Logan replied, laughing. He went on to explain the many moving parts from the moment an order gets taken to when the food goes out the window, and that "if the person managing the whole thing doesn't have a good idea of where all their resources are and where they need to be used most effectively, nothing ever gets done."

Warren responded that Logan's colleagues at the fast food restaurant "are people we need in this fight."

"I'm going to count on you to talk to some of those folks who are working at McDonald's. Can I do that?" she asked.

"Yes, absolutely."

Warren has readily acknowledged the challenges of this person-to-person and small-dollar focused grassroots model. She recently told reporters in Iowa that she was no doubt "leaving money on the table." And unlike many of her competitors, the Warren team has not shared any early fundraising numbers, stoking speculation that the campaign is struggling on this front.

Data from the online fundraising platform ActBlue showed that Warren raised under $300,000 on the day she announced her exploratory campaign on New Year's Eve. That figure pales in comparison to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders' early haul. Using the same small-dollar, grassroots strategy from his first presidential bid in 2016, the campaign said it raised a stunning $10 million in the first week of launching his campaign.

California Sen. Kamala Harris' campaign said she raised $1.5 million in the 24 hours following her announcement in late January, while Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar's team announced raising $1 million in the first 48 hours after her campaign launch.

The Campaign Legal Center's Brendan Fischer told CNN that Warren's announcement foregoing all solicitation of wealthy donors was a "meaningful pledge."

"A candidate voluntarily limiting the amount of time they spend asking wealthy donors for money is a real financial sacrifice, and can have a real impact on the way that money influences our political system," Fischer said.

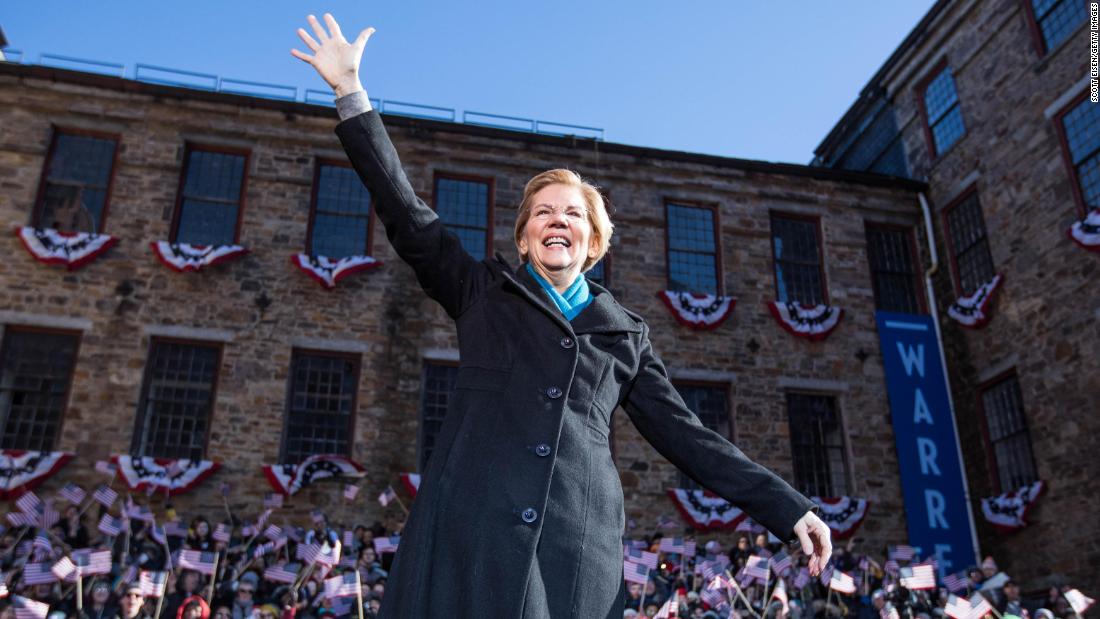

Warren's 'selfie lines'

The line often wraps around the room, sometimes even snaking out of the entrance of the school gymnasium or local community center after Warren's stump speech and question-and-answer session.

What's been dubbed the "selfie line" at the end of every Warren campaign event is key to the senator's grassroots strategy. (Technically, the photos aren't selfies -- a Warren aide helps snap one photo after another in quick succession.)

Asked how much she can learn from these seconds-long interactions, Warren insisted it's more than you would think.

"Sometimes it's an issue that really matters to them and someone will say to me: 'I've got $68,000 in student loan debt. I'm teaching public school. There's no way I can hold this together,'" she told CNN. "Or, 'I have a child with a serious illness and all of her life she's going to have had a pre-existing condition. Please don't let them change the law.'"

"And sometimes it's just to say, 'Can I have a hug?' We do a lot of hugs."

According to the Warren campaign, she has done 29 photo lines this year, spending more than 26 hours posing with more than 9,500 people -- all of whom the campaign hopes will walk away with memorable impressions.

And the campaign is also counting on those voters across the country -- regardless of whether they're sold on Warren or still figuring out who to support in the Democratic primary -- to post their pictures on social media.

"It's going to be everywhere," said Bella Allen, a woman from Long Beach, California, who waited in line to take a photo with Warren after an event in Glendale, California, last month.

Referring to her photo as a "treasure," Allen said she hopes it "inspires people to get out and vote and be a part of the change."

Anthony Marquez, who attended that same event and is supporting Warren, told CNN that he wants to help "get her name out there" -- and perhaps even sway friends who are less tuned into the election.

"I'm from South L.A, and most of my friends are from South L.A. -- a place that does not really vote," Marquez said. "So they can see that we're part of this too and we could do something about it and taking this selfie makes a big impact and I know social media is huge right now."

The Warren campaign has also used social media to learn about potential new supporters.

After the senator addressed a crowd in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, last month in the middle of a snow storm, a woman named Molly tweeted: "Elizabeth Warren knocked it out of the park in Cedar Rapids. I wasn't expecting this, but I'm all on board."

Warren's Iowa team quickly tracked down Molly's number.

"I saw your tweet and I am delighted you are all on board. Let's do this," Warren told Molly, in a video of a phone call that the campaign then tweeted out.

Molly told CNN that Warren's phone call woke her up from a nap.

"It's caucus season," she said. "Anyone to call me to wake me up from a nap, including someone like Elizabeth Warren, isn't that unreasonable."

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Surprise phone calls and 'selfie lines': Inside Elizabeth Warren's grassroots strategy"

Post a Comment