He was known as a lighthearted presence at his previous job, when he was a cantor at Congregation Beth Judah on the New Jersey coast: good for a nip of Scotch after Shabbat services, for talking trash about his beloved New York Giants, for teaching Judaism to children and orchestrating elaborate productions of Purim spiel, the comic plays that commemorate Jews' deliverance from an anti-Semitic emperor.

But that was before seven members of Rabbi Jeffrey Myers' congregation were slaughtered in their sanctuary, their holy place, on Saturday. It was the worst anti-Semitic attack in American history, with 11 killed overall. Each of the three Jewish congregations that meet at Tree of Life synagogue lost at least one member.

"My holy place has been defiled," Myers' said Sunday, echoing the Prophet Ezekiel.

Now, Myers wonders why God would put him in Pittsburgh, where he landed his first job as a rabbi at Tree of Life/Or L'Simcha a little more than a year ago. He wonders if he could have done more to save his flock. He hears the screams of Bernice Simon as her husband of more than 60 years was shot before her eyes, and then he hears her silence.

When he lies awake at night, the rabbi thinks of Psalm 23, which begins, "The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want."

"Well, God, I want!" he said at an interfaith service Sunday in Pittsburgh, channeling the grief and anger of many Americans. "What I want, you can't give me. You can't return these 11 beautiful souls."

Later, Myers recalled how Psalm 23 concludes, with gratitude for a "cup that runs over," and he thought about the outpouring of support that has flowed from hundreds of texts, emails and social-media messages.

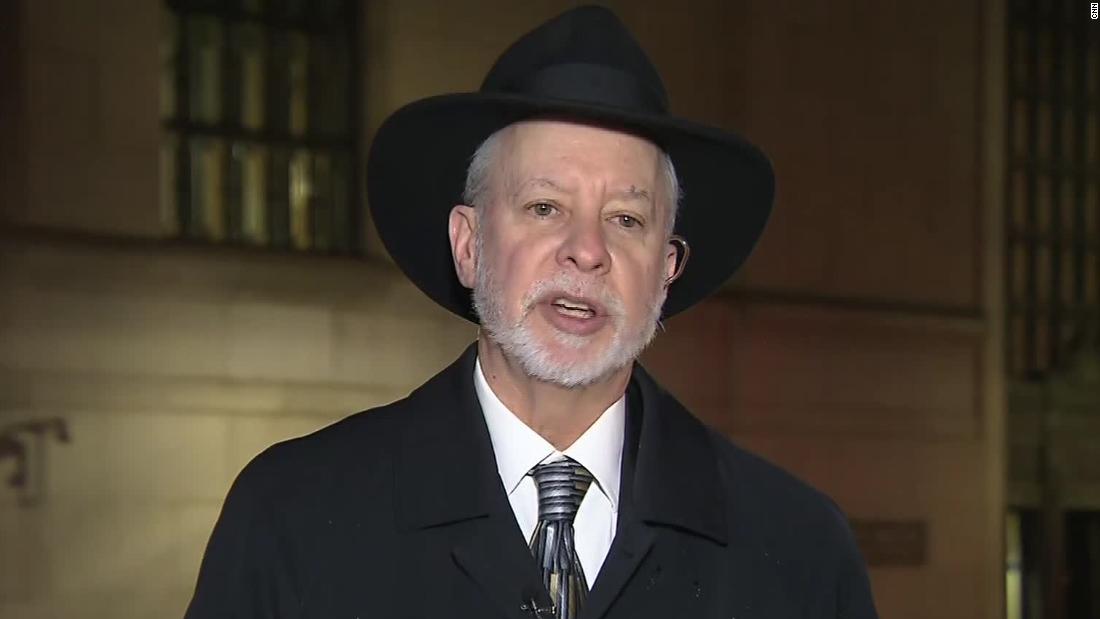

To watch Myers under the media's klieg lights this week, explaining Jewish mourning rituals to President Donald Trump and the first lady, answering questions from countless journalists, or counseling a grieving nation, is to wonder at his composure and apparent kindness. His shear mensch-iness.

As the week wears on, Myers is again preparing for the Sabbath, planning to lead services Friday night and a "unity service" on Saturday, one week after the shooting, bringing together survivors from the three congregations that worshipped at the Tree of Life.

Friends and former colleagues say they are impressed but not surprised by Myers' spiritual stamina.

"He's shouldering the responsibility, but I also know that deep down he is overwhelmed by the events and still doing amazingly well," said Rabbi Aaron Gaber, who worked alongside Myers for seven years at Congregation Beth Judah in Ventnor City, New Jersey. "I am in awe."

But when Myers talks about Psalm 23, it's hard not to think about the middle of David's ancient song.

Between the shepherding Lord and the overflowing cup lays a valley dark with death, the psalmist says. And even for a rabbi who encourages his flock to find the little joys amid life's sorrows, these must be very dark days.

"I'm running on empty," Myers said in a brief email message.

The 'Kiddush Club'

Growing up in Newark, New Jersey, Myers heard a call to join the clergy from a young age, when the cantor of his local synagogue introduced him to the intricacies of Jewish liturgy.

When that cantor had a stroke, Myers stepped in to conduct the congregation's choir, though he was just 15, he told the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle.

In Judaism, the cantor, or hazzan in Hebrew, leads the congregation in singing, sometimes composing new melodies to accompany ancient prayers. In the 20th century, cantors could become as famous as opera singers among American Jews. Today, many cantors also take charge of a congregation's youth education programs, as Myers often did.

After graduating from Rutgers University and the Jewish Theological Seminary, he returned to his love of sacred singing, even if his wife, Janice, sometimes wondered at his passion for the arcane art.

"Mine is a sacred calling," he said at his farewell celebration at Congregation Beth Judah in 2017, "and although Janice will sometimes ask me, 'Do you have to answer the call?' I cannot put God's call to voice mail."

Though Myers took his divine call seriously, he is not a brow-furrowed zealot, Gaber said. After prayers on Shabbat, he would invite fellow worshippers to join his "Kiddush Club," where the only price of admittance was a willingness to sip a nip of Scotch on a Saturday morning.

"Everyone was invited to have a shot of Scotch and enjoy themselves," Gaber said. "That's how he is. He creates a lot of joy."

Myers' tenure at Congregation Beth Judah ended on a sad note, though, when the congregation merged with another synagogue, as many others have in the face of declining religious observance among American Jews.

Beth Judah let him go last year, according to Jewish Voices New Jersey, a newspaper. At his farewell party, Myers thanked everyone from the synagogue's maintenance man to his children, Aaron and Rachel. Most of all, he thanked the people he sang for.

"Thank you to you, my congregants," he said, "for the opportunity to represent you to God in prayer."

While he was at Congregation Beth Judah, Myers quietly became ordained as a rabbi, figuring it could expand his job prospects. It did. Tree of Life/Or L'Simcha hired Myers a few months after he left Congregation Beth Judah.

'A stronger tree'

At his installation ceremony at Tree of Life, Myers opened with a joke: A rabbi finds a box in the attic, which his wife tells him not to open.

Overcome by curiosity, the rabbi pries open the box, finding three eggs and $2,000.

The rabbi's wife told him that she put an egg in the box for every bad sermon the rabbi delivered. "In 20 years, only three bad sermons? That's not bad," the rabbi said.

Um, yeah, the rabbi's wife said, except that every time the box filled with a dozen eggs, she sold them for a dollar.

After the joke, Myers turned serious.

American Judaism is changing, he told members of his new congregation, and, in order to survive, they would have to change as well. They would have to find new ways to reach a rapidly diversifying country.

"This voyage may indeed be treacherous, with storms along the way, but it also holds the promise of clear, calm waters and beautiful vistas," he said. He even donned a captain's hat to demonstrate his willingness to head the ship, according to a transcript of the speech.

Tree of Life will now be noted for a different, tragic reason. Already, it has become a place of pilgrimage for Jews and other well-wishers around the world. Meanwhile, Myers said, the "hard work of healing" still lies ahead.

"We will rebuild to be a stronger tree, offering a new light," the rabbi said at last Sunday's interfaith vigil. "People will come and say, 'Wow, that's how you're supposed to live your life.' "

The audience clapped, and then the rabbi began to sing. The song was a mourner's lament.

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Rabbi Myers heard the screams of his congregation. Now he wrestles with God and his conscience"

Post a Comment